Is great advertising great

because of great ideas?

The J. Walter Thompson Company, once one of the world’s leading advertising agencies, claimed to be the “idea” agency.

In an advertising campaign that ran in Fortune Magazine, in 1934 and 1935, the J. Walter Thompson Company addressed powerful persons in business or industry on the importance of “ideas” in great advertising.

“If J. Walter Thompson Company has distinction,” they explained in one advertisement, “it is the distinction of finding and recognizing and using ideas, related to products, which penetrate the armor of human indifference, and strike the emotional spark with human need.”

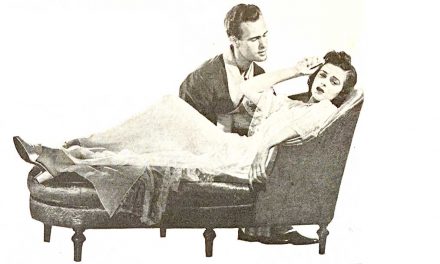

In this advertisement featuring the 11th President of the United States, JWT—as the agency was commonly called in the advertising industry— claimed “It is the ability of advertising men to find a good idea, and recognize it when they have found it, and keep using it that determines their success, and the success of their clients.”

JWT pointed out that a great deal of money is spent for advertising which lacks an idea; for advertising in which the secondary factors—clever language, “technique”, fictitious excitement—masquerade as an idea.

In the “Remember the Alamo” advertisement below, JWT points out that every advertising campaign need the rallying point of an idea. A distinctive conception of the product’s usefulness in terms of human need.

“The smaller the campaign, the greater the need,” the advertisement says. “Sheer weight of space can make a product impressive, but this is an expensive substitute for an idea, and wide open to punishing attack on the day when a worthy competitor arms himself with an idea.”

The J. Walter Thompson Company was incorporated in 1896 by American advertising pioneer James Walter Thompson. It became one the world’s most successful ad agencies on the strength of classic campaigns for brands like Ford, Kraft, Kellogg’s, Unilever, and the US Marines. In November 2018 J. Walter Thompson merged with another major agecny Wunderman to become Wunderman Thompson.

The company initially was a brokerage; it bought space in newspapers and sold that space to advertisers. As more and more local businesses adopted advertising to promote trade, these early “wholesalers” evolved from simply being sellers of space: Writers and artists were added to the sales force selling the space—since selling space was achieved more easily when the advertiser was shown visual examples of how an advertisement might actually look in a newspaper. This was the forerunner of the agency in the role of rendering a complete service to the advertiser.

Enterprising agencies representing major advertisers entered into contracts with newspaper publishers that paid commission for space sold.

Agencies earned commissions varying from 5% to 25%. By World War I, the commission became standardized at 15%. And when outdoor advertising became a powerful medium and when broadcast media entered the market, the commission system was adopted by all media.

And so evolved a unique feature of advertising agencies: the agency created advertisements for the advertiser, technically worked for the advertiser, but was paid by the media!

An agency is appointed by an advertiser to handle his account, but it makes contracts with media in its own name, as an independent contractor and not as anyone’s legal agent with respect to the purchase of space and time. That is to say, if a client doesn’t pay its bills, the agency is nevertheless responsible and, conversely, if the agency defaults, the medium will not look to the advertiser for payment.

This standardization of commission also included “agency recognition” granted at first by individual publishers but eventually granted by associations to which media belonged. Associations granted recognition to agencies that already had advertisers, the ability to serve those advertisers and financial capacity to meet the credit standards of the media.